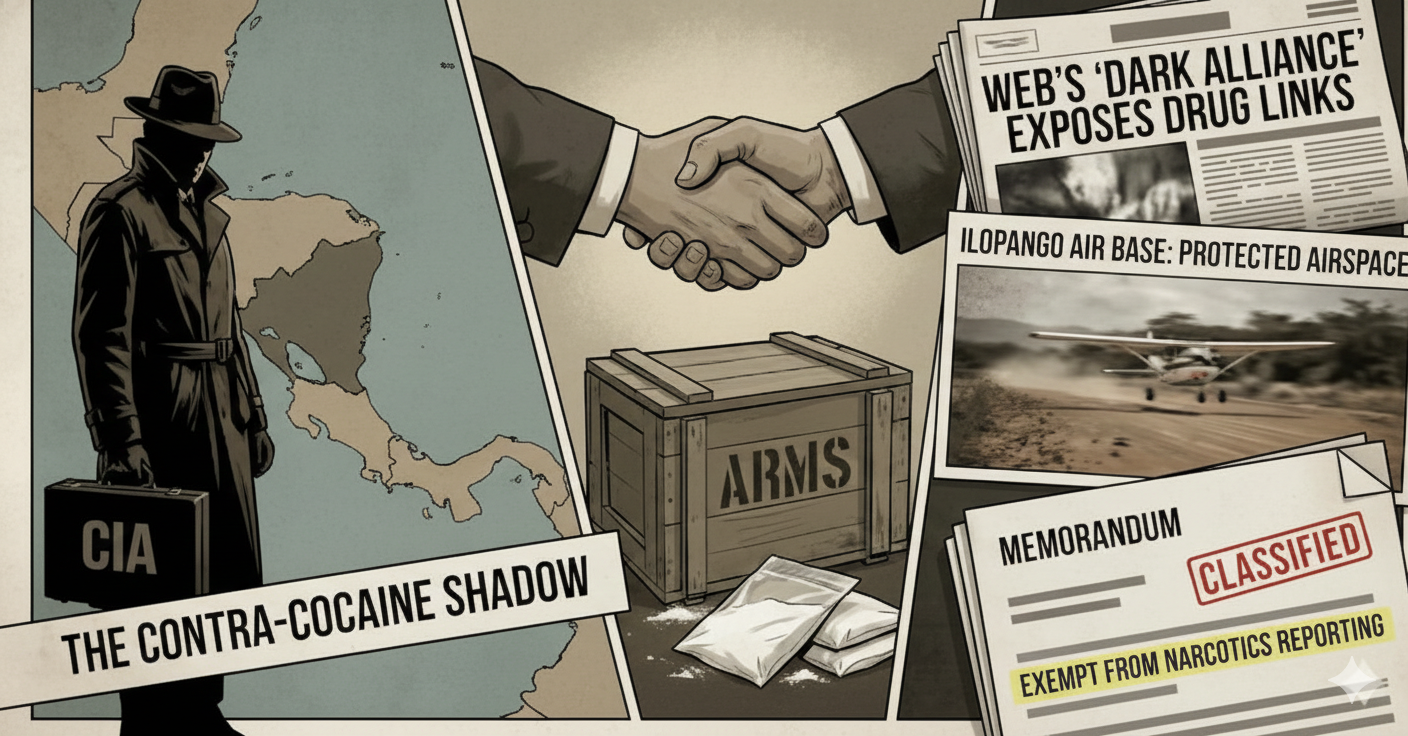

The intersection of national security and criminal enterprise has rarely produced a more enduring controversy than the allegations of CIA involvement in the 1980s cocaine trade. What began as a series of whispers during the Reagan administration’s “Secret War” in Nicaragua eventually snowballed into a national crisis that questioned the ethical foundations of American intelligence operations.

To understand the depth of this issue, one must look past the headlines and examine the systemic mechanisms the “lapses” and “memos” that allowed a drug-funded insurgency to operate under the umbrella of US foreign policy.

The Geopolitical Trade-off

In the early 1980s, the White House was singular in its focus: halting the spread of communism in the Western Hemisphere. The Sandinista government in Nicaragua was the primary target, and the Contras a collection of rebel groups were the chosen instrument. However, when Congress passed the Boland Amendment to limit US funding for the rebels, the operation moved into the shadows.

This vacuum created a desperate need for funding, and the Contras found it in the vast, lucrative cocaine trade flowing north. Intelligence assets on the ground were faced with a choice: report the drug trafficking and lose their anti-communist allies, or look the other way to keep the mission alive. History shows they chose the latter.

The “Dark Alliance” and the Crack Epidemic

The controversy reached a boiling point in 1996 with journalist Gary Webb’s investigative series, “Dark Alliance.” Webb’s reporting for the San Jose Mercury News made a explosive claim: that a drug ring linked to the CIA had funneled tons of cocaine into Los Angeles, essentially fueling the crack epidemic that devastated American inner cities.

While Webb’s work was later criticized for overstating the direct agency “link” to specific dealers like Freeway Rick Ross, the subsequent fallout forced the government’s hand. The public demand for transparency led to the 1998 report by CIA Inspector General Frederick Hitz, which remains the most definitive, if troubling, look into the agency’s internal conduct.

Institutionalized Silence: The 1982 Memo

The Hitz report officially cleared the CIA of “direct complicity” or profit-sharing. However, it revealed a bureaucratic framework that seemed designed to facilitate ignorance.

One of the most damning discoveries was a 1982 Memorandum of Understanding between then-CIA Director William Casey and Attorney General William French Smith. This legal agreement explicitly exempted CIA agents and assets from the mandatory reporting of narcotics violations. For over half a decade, intelligence officers were legally permitted to ignore drug crimes committed by their partners in the field. This wasn’t a “lapse” in the traditional sense; it was a policy of authorized silence.

Protected Airspaces and “Willful Blindness”

The operational reality of this policy was seen at sites like Hangar 4 at the Ilopango air base in El Salvador. This facility was a hub for the clandestine supply network managed by figures like Oliver North. Despite repeated warnings and specific suspicions from the DEA that the hangar was being used for drug shipments, it remained largely off-limits to law enforcement.

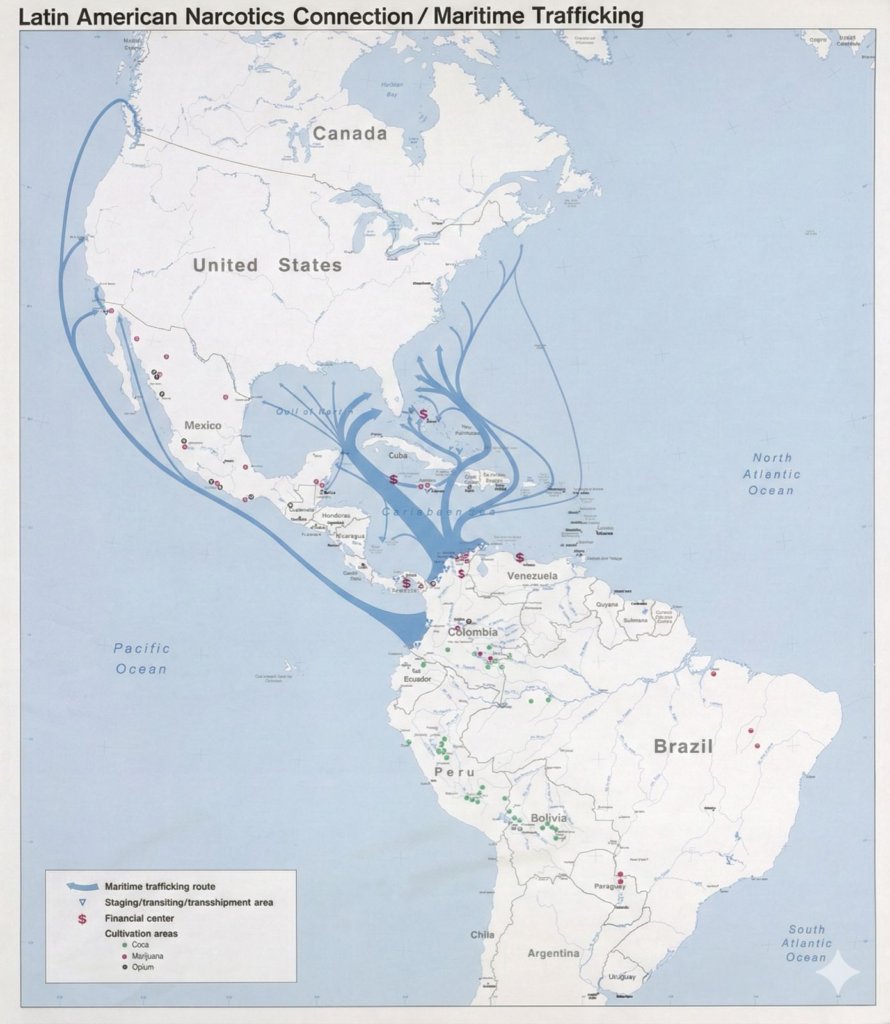

This “willful blindness” created a protected corridor for traffickers who were also providing logistical support to the Contra cause. As long as the planes were moving weapons south, the agency was remarkably uncurious about what they were carrying on the return flight north.

The Legacy of Gray Alliances

The story of the Contras and cocaine is more than a historical footnote; it is a case study in the “cost of doing business” in covert warfare. It illustrates a recurring pattern in intelligence: when a government aligns itself with unsavory actors in regions dominated by illicit economies, the integrity of the state is inevitably compromised.

The 1989 Kerry Committee report eventually concluded that the US government was indeed aware of the Contra-drug links and that the State Department had even made payments to known traffickers. Today, this era serves as a stark reminder of what happens when ideological warfare takes precedence over domestic law and social health. The “lapses” of the 1980s weren’t just bureaucratic errors, they were the predictable result of a strategy that prioritized the defeat of an ideology over the protection of its own citizens from the scourge of narcotics.