– By Animesh Singh

When Pakistani and Afghan forces exchanged heavy fire along the Durand Line recently, the headlines suggested another familiar border skirmish. Yet beneath the gun smoke lies a story far older and far more complex — one that mixes colonial cartography, tribal identity, harsh geography, and shifting global alignments into a volatile frontier stew.

A Colonial Line That Never Healed

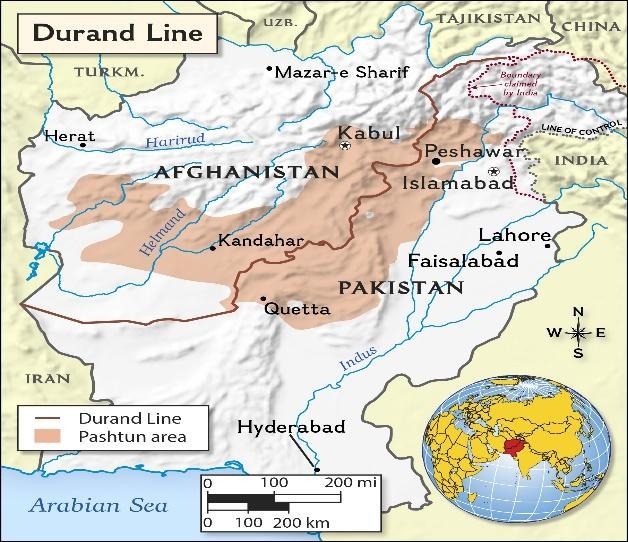

The origins of this recurring crisis trace back to 1893, when Sir Mortimer Durand of British India and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan of Afghanistan drew an arbitrary line stretching over 2,600 kilometres — from the Iranian border near Nimroz through the tribal belts of Khyber Pass, North Waziristan, Khost, and Nangarhar, right up to the icy corridors of Wakhan near China.

The Durand Line served imperial convenience, not ethnic coherence. It split the Pashtun heartland in two, leaving millions of tribesmen straddling both sides with kinship ties stronger than state allegiance.

When Pakistan inherited this boundary in 1947, Afghanistan refused to recognise it formally. Kabul still considers it an imposed line, while Islamabad treats it as settled international law. That basic disagreement ensures that every border post, every fence, and every stray bullet is loaded with political meaning.

Mountains That Mock Mechanisation

Geography compounds history’s burden. The border slices through the Hindu Kush, Spin Ghar, and Karakoram ranges — landscapes of forbidding peaks and narrow gorges. Military strategists know that tanks and armoured columns lose purpose here: tracks are few, ambush points infinite.

Even airpower offers limited precision in this terrain. Airstrikes risk collateral damage in thickly populated valleys where insurgents and civilians coexist. Each errant bomb deepens resentment and invites retaliation, turning tactical victories into strategic defeats.

It is little surprise that guerrilla warfare, not conventional combat, dominates this frontier. Local fighters — often drawn from tribal militias or militant offshoots — understand the topography, can blend with civilians, and strike where the state’s writ thins.

For modern militaries, that means attrition without conclusion — the same dilemma that confounded both Soviet and American forces in Afghanistan.

The Pashtun Paradox

At the heart of the tension lies the Pashtun question. Pashtuns form the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and a major one in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces. Their shared language, traditions, and tribal code (Pashtunwali) bind them beyond national borders.

This dual identity makes policing the frontier extraordinarily difficult. Any heavy-handed operation risks alienating local tribes whose cooperation is vital for intelligence and stability. For Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers — themselves overwhelmingly Pashtun — the optics of conceding on the Durand Line are politically perilous; it would be seen as a betrayal of their ethnic brethren.

For Pakistan, however, allowing porous frontiers means enduring the return of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) attacks from Afghan soil. The clash, then, is not merely territorial — it is an ethnic and ideological dilemma with no clean military fix.

Strains Within, Threats Without

Both countries are also battling internal fires. Pakistan faces a resurgence of militancy in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, an economic downturn, and political flux. The Taliban regime, meanwhile, is grappling with isolation, financial collapse, and the challenge of governing a fractured nation.

Islamabad’s army is stretched thin: redeploying troops from the eastern border with India to plug the western frontier leaves vulnerabilities elsewhere. This shift, however, has also had an unintended consequence — a temporary dip in cross-border terrorism along the Line of Control (LoC), as Pakistan focuses westward.

Yet, such rebalancing cannot continue indefinitely; strategic overstretch and morale fatigue are real risks.

Shifting Alignments and Economic Undercurrents

The geopolitical context is equally fluid.

Pakistan’s quiet realignment with Washington, signalled by renewed intelligence cooperation and economic overtures, marks an attempt to diversify away from over-dependence on Beijing. But this balancing act complicates Islamabad’s relations with China, which has poured billions into the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The western frontier’s instability now jeopardizes CPEC’s extensions through Balochistan and Khyber. Attacks on Chinese nationals and projects have already unsettled Beijing. If the border heats up further, China may press Pakistan for tougher internal controls — or even explore a more direct relationship with the Taliban to secure its interests.

For Beijing, Afghanistan also represents opportunity: mineral resources, a trade corridor to Central Asia, and strategic leverage over regional rivals. Hence, some analysts believe China could quietly support Taliban consolidation — not militarily, but through economic carrots and diplomatic shielding.

India’s Calculated Engagement

India, once a staunch critic of the Taliban, has recalibrated its stance. New Delhi now maintains limited diplomatic contact and humanitarian channels with Kabul. The shift is pragmatic — to preserve development projects, safeguard its embassy footprint, and keep watch over Pakistan’s western flank.

While India remains wary of Taliban ideology, it recognises that complete disengagement only cedes influence to rivals. Thus, India’s current policy threads a careful line: cautious contact without endorsement.

Beyond the Border — a Strategic Web

The Pakistan–Afghanistan clashes are not isolated eruptions. They tie directly to broader regional flux — Washington’s post-withdrawal recalibration, Beijing’s investment anxieties, Tehran’s growing assertiveness, and New Delhi’s watchful pragmatism.

Each actor has stakes; each stands to gain or lose depending on how Islamabad and Kabul manage the next few months.

What Next?

Most likely, both sides will cool tempers under mediation from Qatar, Turkey, or the Gulf states, only to resume hostilities later. The cycle will repeat because the root problem — an unrecognised colonial boundary cutting through living tribes — remains untouched.

Pakistan’s dilemma is particularly acute. It cannot afford an open western front, yet it cannot ignore cross-border attacks. Afghanistan, meanwhile, cannot admit the Durand Line without eroding its Pashtun legitimacy. The result: a stalemate disguised as sovereignty.

A Line That Still Bleeds

As historian Sir Alfred Lyall once observed of imperial boundaries, “Lines on maps are easier to draw than to live behind.”

The Durand Line is exactly that — a line easier drawn than accepted.

Until both Islamabad and Kabul find the political courage to transform that line from a wall of suspicion into a corridor of cooperation, the mountains of the Hindu Kush will continue to echo with gunfire — and silence, once again, will not mean peace.

Insightful and absolutely worth reading!! 🙌