India’s indigenous aero‑engine programme has long been viewed through the prism of the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas. However, recent remarks by DRDO Chairman Dr. Samir V. Kamat offer a more nuanced and technically grounded picture of where the Kaveri engine stands today and where it is realistically headed.

“Kaveri engine, in its original form, has not delivered the thrust that is required for the LCA. The engine is working very well; it has given us a thrust of 72 kilonewton. But the LCA needs a thrust of 83–85 kilonewton. So, it’s not going to be used in the LCA, but we are using the derivative of the Kaveri engine for our unmanned combat aerial vehicle.” ~ Dr. Samir V. Kamat, Chairman, DRDO

This statement, while seemingly a setback, actually marks a strategic maturation of India’s aero‑engine ecosystem.

Understanding the Thrust Gap: Why LCA and Kaveri Diverged

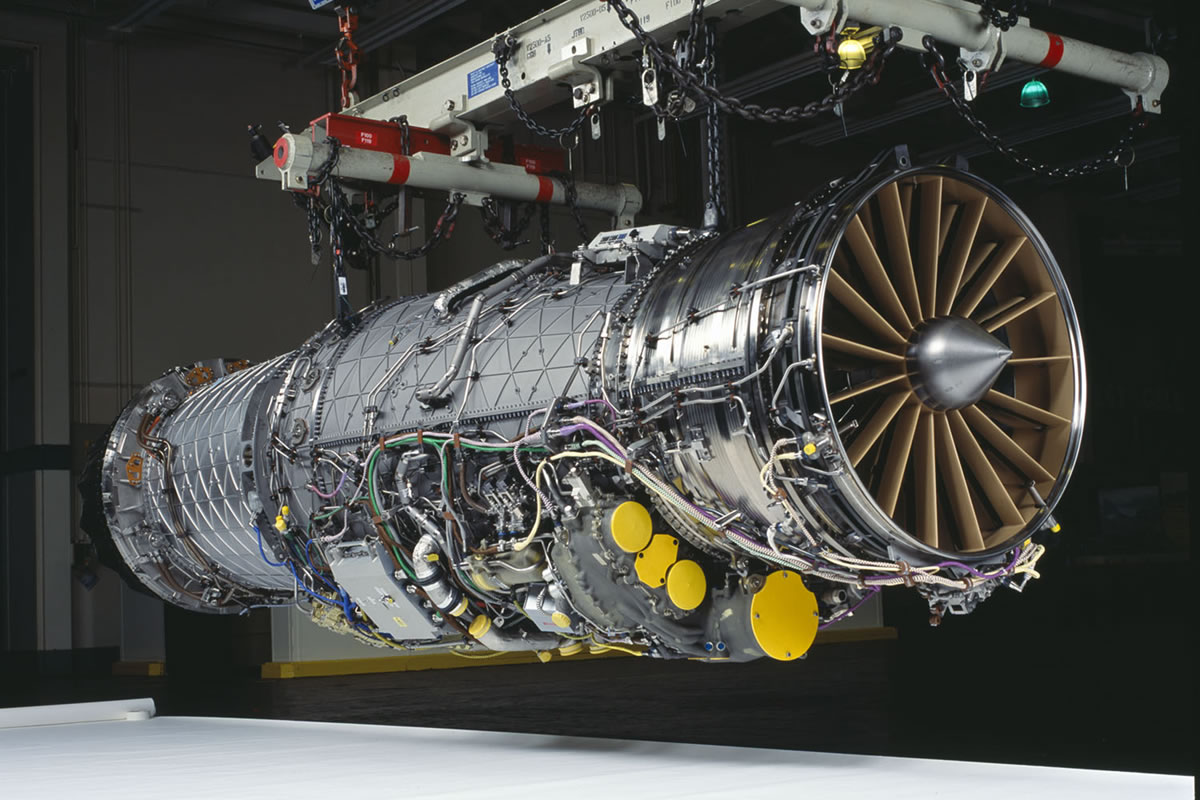

The original GTRE Kaveri (K9/K10) engine was conceptualised in the late 1980s to power a lightweight fourth‑generation fighter. Over time, the LCA Tejas evolved significantly gaining weight due to enhanced avionics, structural reinforcements, multi‑role capability, and stringent safety margins.

From an engineering standpoint, the mismatch is clear:

- Kaveri achieved ~72 kN thrust with afterburner, which is a credible figure for a first‑generation indigenous turbofan.

- LCA Mk1/Mk1A require ~83–85 kN, driven by thrust‑to‑weight ratio, hot‑and‑high performance, and carrier‑like safety margins during take‑off.

Closing a 10–13 kN thrust gap is not an incremental upgrade, it implies fundamental changes in core temperature, pressure ratio, materials, cooling technologies, and turbine design. These are areas where even established engine OEMs take decades to mature.

“The Engine Works Very Well”: A Crucial but Overlooked Detail

Dr. Kamat’s assertion that the Kaveri “works very well” is not a diplomatic statement, it is a technical one.

The Kaveri programme has successfully demonstrated:

- Stable core operation across flight envelopes

- High‑altitude relight capability

- Endurance testing exceeding thousands of hours

- Safe operation without afterburner in derivative configurations

In aero‑engine development, achieving a reliable, certifiable core is often the hardest milestone. Thrust shortfall, while critical for a manned fighter, does not negate the engine’s engineering value.

Strategic Shift: Kaveri Derivative for UCAVs

The most consequential takeaway from DRDO’s position is the repurposing of the Kaveri into unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs).

Why UCAVs Are a Better Fit

It is important to clarify a frequent misunderstanding: the Kaveri’s application on UCAVs is not driven by safety or risk-avoidance concerns. As DRDO leadership has made clear, the engine is fundamentally sound and performs reliably. The decision is dictated purely by thrust requirements and mission profiles, not by doubts over safety or maturity.

From an engineering perspective, unmanned combat platforms are designed around different propulsion envelopes:

- UCAV thrust requirements align closely with Kaveri’s demonstrated output in the ~70 kN class

- Mission profiles emphasise endurance, efficiency, and sustained cruise, rather than rapid climb or high thrust-to-weight ratios

- Afterburner-independent operation is acceptable and often desirable due to fuel efficiency and lower infrared signature

In contrast, the LCA’s requirement of 83–85 kN is driven by manned-fighter performance criteria such as hot-and-high take-off margins, acceleration, and recovery from adverse flight regimes. These demands exceed what the Kaveri was originally optimised for.

Therefore, the UCAV route represents technical alignment, not compromise allowing the Kaveri to operate squarely within its validated thrust envelope while delivering an indigenous propulsion solution for combat aviation.

This approach is consistent with global aerospace practice, where engines are fielded first on platforms whose thrust and mission requirements match the engine’s core design, before being evolved further.

Kaveri Is Not a Failure : It Is a Foundation

Judging the Kaveri engine solely by its non‑selection for LCA oversimplifies a deeply complex engineering journey. Aero‑engine mastery is cumulative. Every successful run, failure mode, and redesign feeds the next generation.

The Kaveri programme has already enabled:

- India’s independent engine test infrastructure

- Expertise in single‑crystal blades, combustors, and FADEC systems

- International collaboration frameworks (Safran etc.) built on parity rather than dependency

In strategic terms, this is how sovereign propulsion capability is built—not through a single leap, but through controlled, iterative progress.

Conclusion: Realism Over Rhetoric

DRDO’s clarity on the Kaveri engine marks an important shift from aspirational rhetoric to engineering realism. The engine may not power the LCA, but it will power something equally important: India’s confidence in designing, testing, flying, and fielding its own military turbofans.

In aerospace, success is rarely linear. The Kaveri’s transition from a manned fighter engine to a UCAV workhorse may ultimately prove to be its most strategically valuable contribution.