In this third and final article of the series, we question whether Larsen & Toubro and Spain’s Navantia, with their Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) system on the S-80 submarine, were truly serious contenders in India’s P75I submarine program, or if they were unknowingly used as tools to serve other interests. We explore whether India’s complex defense procurement policies and the hidden strategies of global defense contractors pulled L&T-Navantia into a situation they didn’t fully grasp.

India’s Complex Procurement Policies

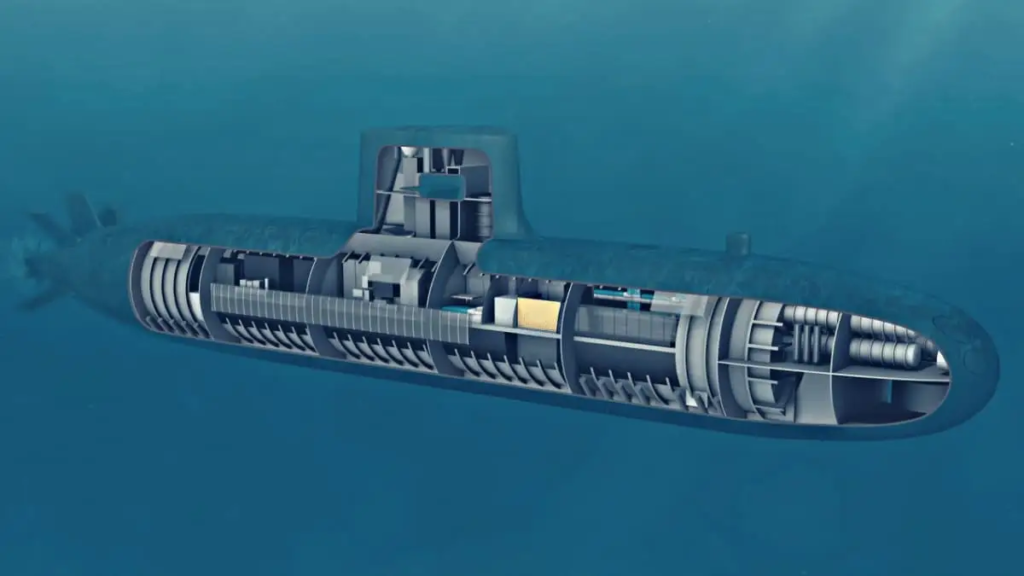

India’s defense procurement processes are notorious for their complexity, especially when it involves a foreign vendor who becomes the sole supplier of a particular system. The P75I submarine program, a crucial project for the Indian Navy to modernize its underwater fleet, has been marked by such complexities. The program’s stringent demands, particularly the requirement for a proven Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) system, drove several global submarine manufacturers out of the race, leaving only a few viable options for India.

L&T-Navantia, looking to secure their first order, saw this as an opportunity. They offered flexibility in terms of technology transfer and local sourcing, making their offer more appealing to India. However, what L&T-Navantia did not realize at the time was that they were being drawn into a situation that was not what it seemed on the surface.

The AIP Requirement: A Decisive Factor

The pivotal element in the P75I program was the Indian Navy’s insistence on a proven AIP system. ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) had a distinct advantage here, as their AIP system is a proven technology already integrated into submarines. This gave TKMS a clear edge over Navantia, whose S80 submarine had not yet integrated an operational AIP system.

Although Navantia and India’s DRDO had developed their own AIP systems, they had only been tested as standalone units, not in full integration with submarines. For India, which had hoped to integrate DRDO’s AIP with its Kalvari-class submarines, this unproven status became a stumbling block. The Indian Navy required a fully integrated and operational AIP system to move forward, and by that measure, Navantia was not a suitable candidate for the P75I program.

From a technical perspective, the difference may seem minor. Both DRDO’s and Navantia’s AIP systems had been tested under conditions similar to real operational scenarios. However, the Navy’s strict demand for proven integration became a convenient filter to disqualify competitors if needed. By this logic, Navantia should not have even made it to the final stages of the bidding process.

ThyssenKrupp’s possible Tactical Play

While Navantia was grappling with the AIP issue, TKMS it seems had its own agenda. The German defense giant was in the midst of negotiations to sell its marine systems division to US-based Carlyle Group. The P75I contract represented a major opportunity to boost its valuation before finalizing the deal with Carlyle.

In early stages of the P75I process, TKMS had walked away, claiming that the Indian Navy’s demands were too high. However, as the Carlyle negotiations advanced, TKMS re-entered the P75I competition. They understood that if Navantia were disqualified, the procurement would become a single-vendor situation with TKMS as the sole remaining contender—a scenario that India’s defense procurement rules do not easily allow. Not that is is impossible but too cumbersome and “time-consuming”, which TKMS doesn’t have given the ongoing due diligence for sale.

TKMS’s return to the process, therefore, had little to do with a renewed interest in the Indian Navy’s requirements. It seems it was all about inflating the company’s value by positioning themselves as the leading contender in a critical defense deal.

Navantia, without realizing it, was brought in as a pawn to maintain the appearance of competition and prevent the procurement from turning into a single-vendor affair. This allowed TKMS to stay in the race without overtly violating procurement rules.

The Indian Navy’s Strategic Vulnerability

As explored in Part 1, the P75I program is of critical importance to the Indian Navy, which faces significant operational risks due to its aging submarine fleet. TKMS’s tactical re-entry into the bidding process has delayed progress, and the protracted negotiations are something the Indian Navy cannot afford. If the procurement process is drawn out for years, it could leave the Navy without the necessary capabilities at a time when India’s maritime security needs are growing.

The situation mirrors past procurement delays, where drawn-out negotiations and constant renegotiations over technical specifications have delayed vital defense acquisitions. Given TKMS’s use of the P75I contract as leverage in its Carlyle negotiations, there is a significant risk that these delays could repeat.

Overall, Navantia’s S80 submarine was never truly in the running for India’s P75I program. The “Non Integrated” status of its AIP system should have disqualified it early on, but the company was kept in the process as a tactical maneuver to prevent a single-vendor scenario. This move was designed to allow ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems to re-enter the competition and use the Indian Navy as a tool to inflate its value ahead of a potential sale to Carlyle.

Navantia, unfortunately, found itself being used in a situation beyond its control. Although the S80 is a capable submarine with potential once its AIP system is fully integrated and proven, its involvement in the P75I program was more about creating the illusion of competition than a genuine bid for the contract.

Looking forward, the Indian Navy must remain vigilant in its procurement process. Delays in acquiring new submarines could severely affect its operational readiness, and the Navy must avoid becoming a bargaining chip in the broader strategies of global defense contractors. At the same time, should Navantia prove its AIP system, its S80 submarine could present a viable option for future projects, with the added benefit of technology transfer and local industry involvement—elements critical to India’s long-term defense ambitions.

The P75I program serves as a reminder of the intricate dynamics at play in international defense procurement, where the interests of foreign contractors often do not align with the urgent needs of the host nation.

Looks similar to torpedo deal where other party was kept in contention just to avoid single vendor situation &avoid cancellation of tender.

with indigenous system developed and tested for integration, any bid or interest for foreign technology needs to be avoided. both l&t and mdl are playing for ulterior motives to deter make in India

New Leadership team in L&T is very novice.

Very averse to developing well-wishers in Delhi

So your entire hypothesis is that Indian Navy did not hv a good understanding of

it’s own requirements, as well as the competitors, L&T Navantia Team is a bunch of novices and TKMS came in only because they want to increase their valuation and not necessarily to effect a sale! How much are you paid by potential competition to write such nonsense?

You think that its possible for an Indian company to buy TKMS with a much more inflated value? Or you think that the europeans wont allow that to happen to an eastern nations company?

This article forgets One fact : TKMS AiP only exists for a different size of submarine and furhermore a new sibamrine design should be required to accomplish the Indian demanda. HT