In the past, Lloyd Austin, the United States Secretary of Defense, highlighted the potential for collaboration between the United States and India in the joint production of armored vehicles in India. This statement sparked interest and discussions about the future of armored vehicle development and production within India, particularly in collaboration with a major global defense player like the United States.

Recently, this topic resurfaced during a meeting between Jake Sullivan, the U.S. National Security Advisor, and Ajit Doval, India’s National Security Advisor. The conversation, however, took on a more cryptic tone, with terms like “possibility” and “land system” replacing direct references to specific vehicles such as the Stryker. This subtle shift in language suggests a cautious yet ongoing dialogue about the potential for such a partnership.

The roots of this discussion can be traced back to the Yudh Abhyas 2009 exercise held in Babina, India. During this joint military exercise, the Stryker armored vehicle was showcased and left a significant impression on the Indian armed forces due to its advanced capabilities and performance.

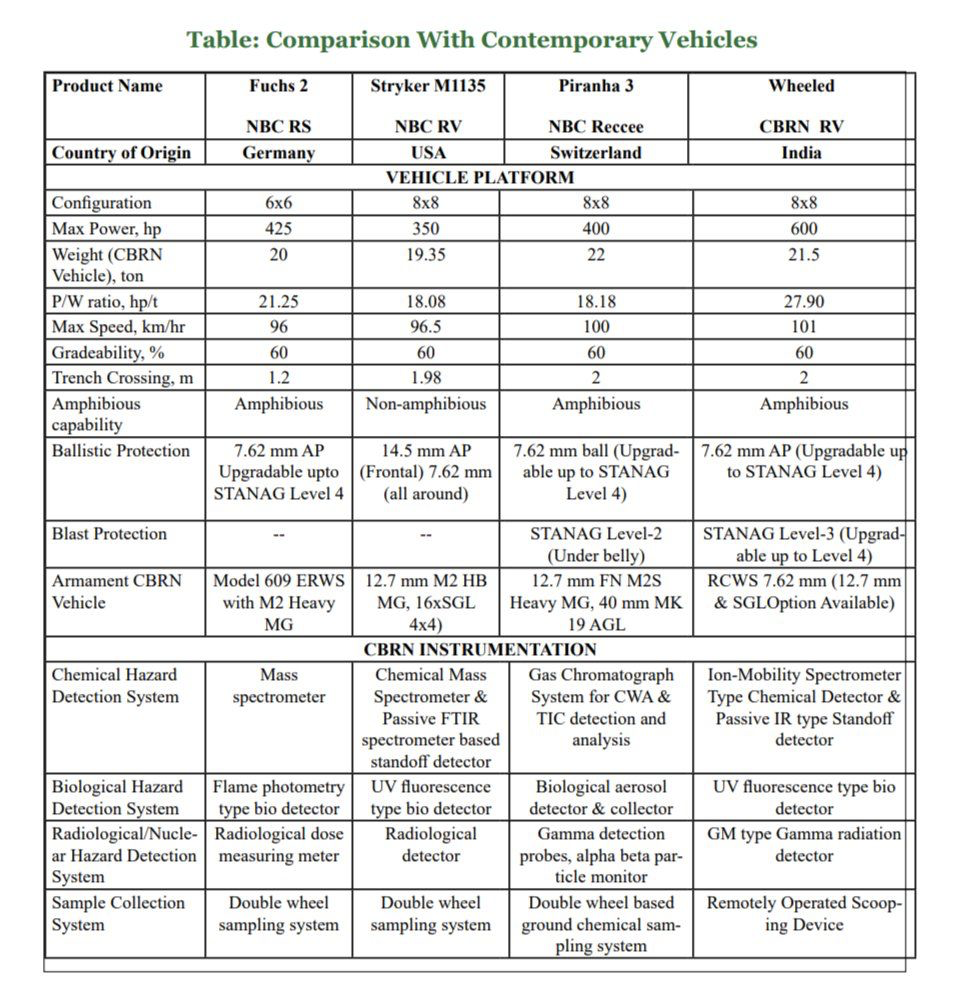

Since then, India’s defense landscape has evolved considerably. The Tata Kestrel, designed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and manufactured by Tata, has already been inducted into the Indian services. Additionally, an improved variant of a wheeled armoured personnel carrier, tailored for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) roles, was unveiled by a collaboration between Mahindra and DRDO. These developments highlight India’s growing competence in producing indigenous armored vehicles that meet the specific needs of its armed forces.

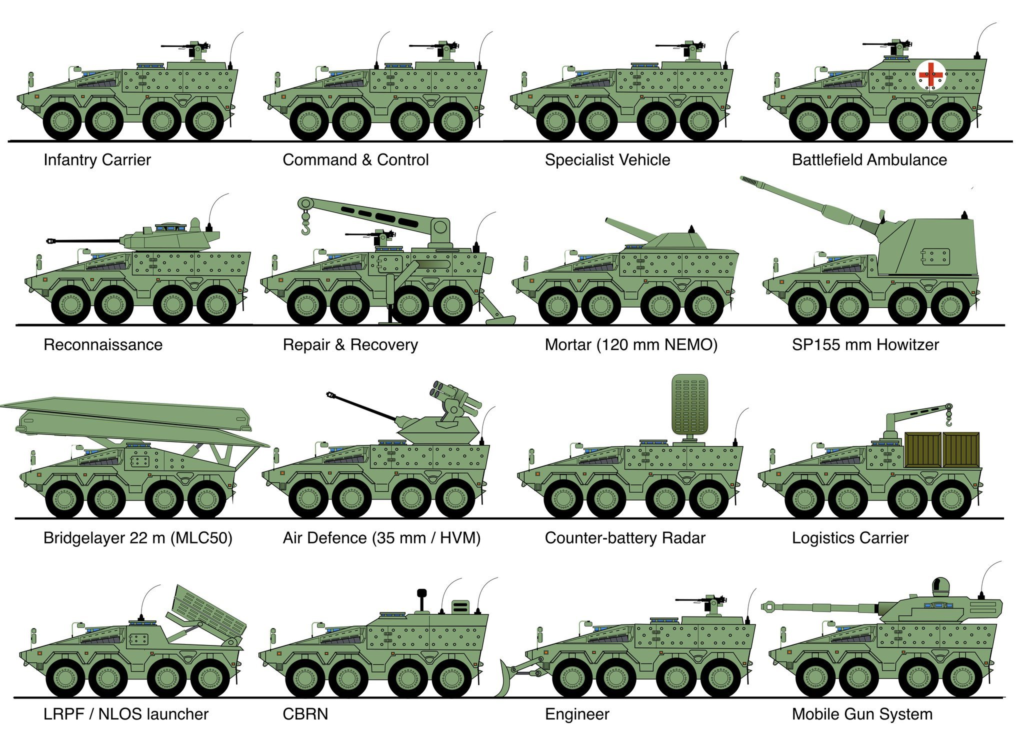

Given the availability of these advanced domestic systems, the proposition of assembling the Stryker in India raises critical questions. India should focus on converting the existing variants of Tata and Mahindra vehicles into a diverse array of specialized vehicles similar to the Stryker family.

This approach would include the development of:

- M1126 Infantry Carrier Vehicle (ICV)

- M1127 Reconnaissance Vehicle (RV)

- M1128 Mobile Gun System (MGS)

- M1129 Mortar Carrier (MC)

- M1130 Commander’s Vehicle (CV)

- M1131 Fire Support Vehicle (FSV)

- M1132 Engineer Squad Vehicle (ESV)

- M1133 Medical Evacuation Vehicle (MEV)

- M1134 Anti-Tank Guided Missile Vehicle (ATGM)

- M1135 Nuclear, Biological, Chemical, Reconnaissance Vehicle (NBCRV)

- M1296 Dragoon

Representational Images below

Introducing the Stryker, even if assembled domestically, could potentially undermine India’s burgeoning defense industry. It would not only diminish the prospects of indigenous products but also sow distrust among domestic manufacturers about the intentions of Indian policymakers. This scenario represents a precarious path for India, where the adoption of foreign systems at the expense of homegrown innovation could stifle the development of similar advanced defense technologies by Indian companies.

Moreover, the potential for export must be considered. Currently, at Eurosatory 2024, India is showcasing its indigenous weapons. If India opts to induct an American system alongside its existing domestic systems, it could negatively impact the appeal of Indian offerings on the global market. Prospective buyers may question the reliability and competitiveness of Indian defense products if India itself is seen preferring foreign alternatives.

Overall, while the exploration of joint production opportunities with the United States may appear as a valuable avenue for strategic collaboration, it is imperative that India prioritizes and fosters its domestic defense industry. Emphasizing the development and diversification of indigenous armored vehicle variants will ensure that India’s defense capabilities remain robust and self-reliant, ultimately supporting the nation’s long-term strategic interests and enhancing its position in the global defense market.

No Strykers please